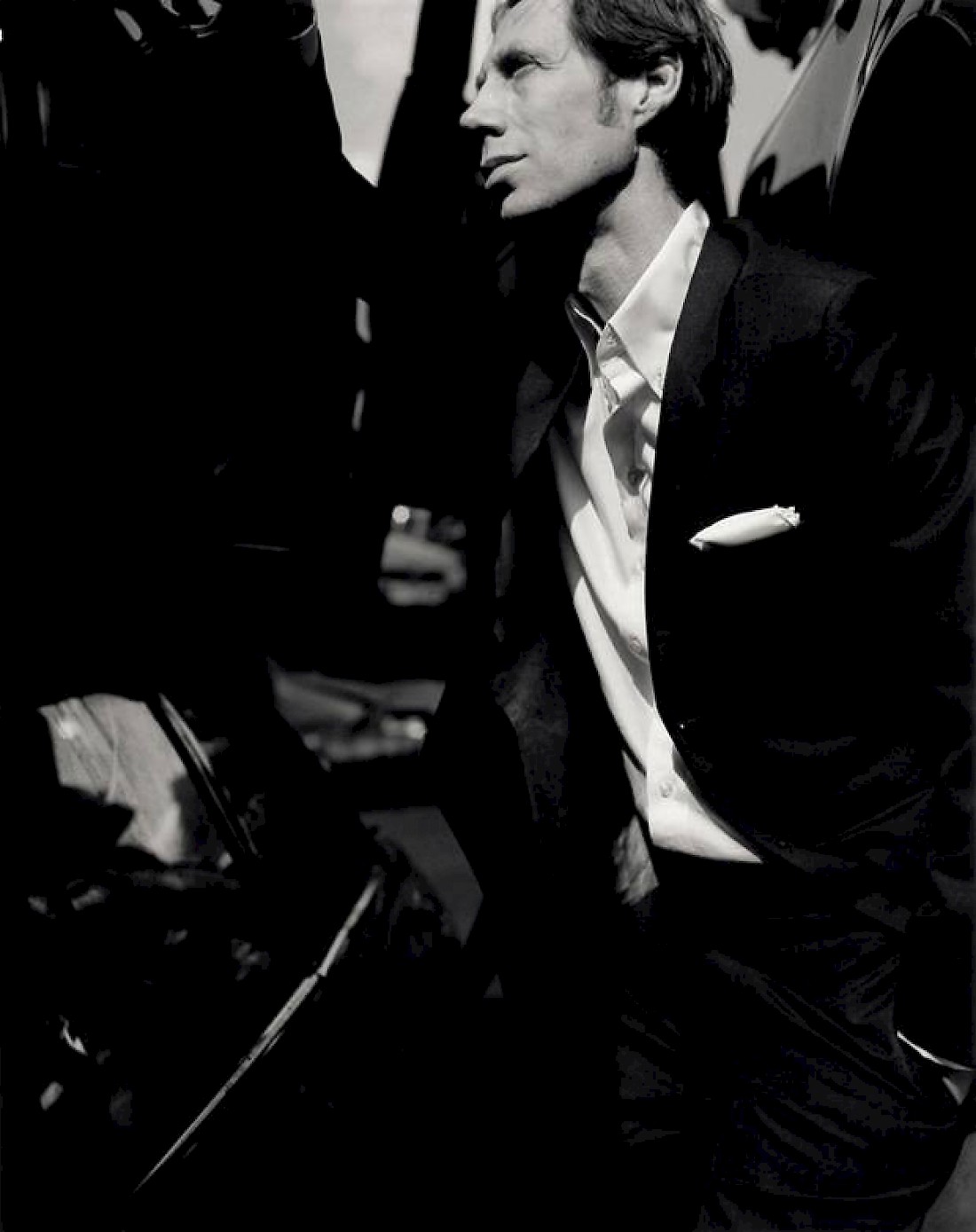

Digital manipulation, unconventional models, streaming shoots live on the net – Nick Knight has torn up the rule book on fashion photography. Susannah Frankel meets a shock tactician.

"The most brilliant thing about photography is that it's a passport into any social situation whatsoever," says Nick Knight. "It's a ticket to photograph the President of the US, or a heroin addict in Camden, or a prostitute in Paris, or the biggest recording star in the world. Becoming a photographer is a way of finding out about people – finding out about life – and experiencing what they experience."

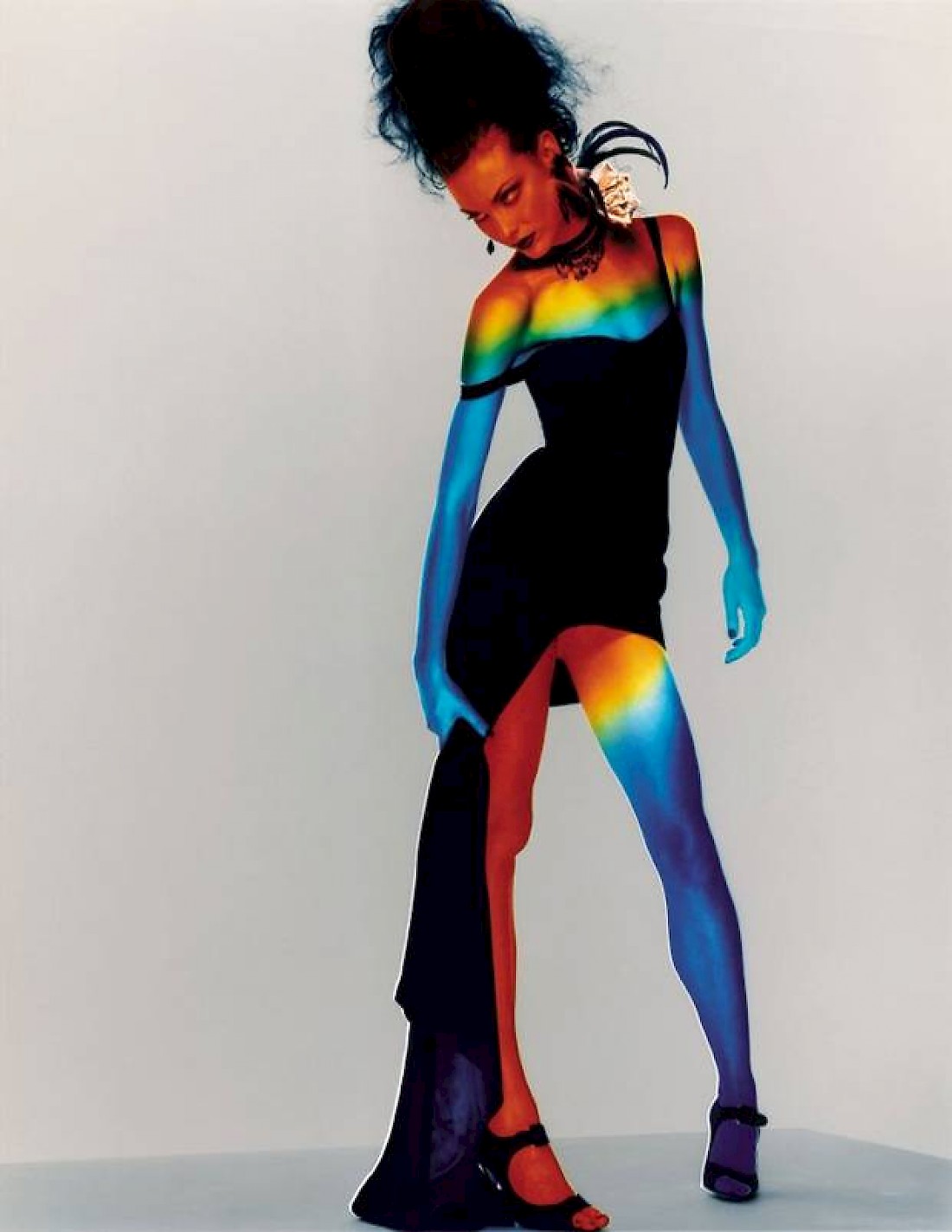

Over the past 30 years, Knight has given the world – and the world of fashion in particular – some of its most arresting, inspiring and innovative imagery. From capturing the extraordinary early designs of Yohji Yamamoto to the equally remarkable curves of a young Sophie Dahl, from still lives of delicate flowers to Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Gisele Bündchen and a galaxy of glossy stars – this restless spirit has challenged preconceptions of what is possible, or indeed beautiful, both technically and aesthetically.

Today, the first major retrospective of his work is published in book form and a luminescently lovely affair it is too. As well it might be. Knight gave up his summer holiday to go to China and oversee the printing – an example of his fanatical attention to detail. "I can tell you, it wouldn't have looked like this if I hadn't," he laughs. It is one of his more admirable characteristics that this near-pathological precision might apply equally to a film he is making for an up-and-coming young designer who's as poor as the proverbial church mouse as it might to a global advertising campaign that will appear on billboards in New York, Tokyo or Beijing. It's not all about money.

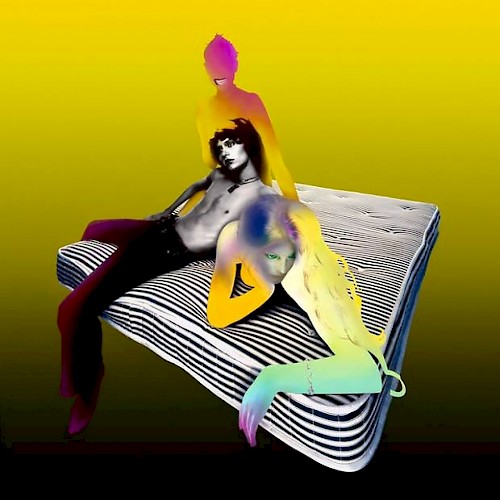

In central London, meanwhile, an exhibition celebrating the 10th anniversary of his pioneering website, SHOWstudio.com, is in full flow at Somerset House. Contributors to the site are varied: as well as just about any designer/model/photographer/stylist worth their credentials, artists, musicians and film directors all feature. At the exhibition, meanwhile, visitors are met by a larger-than-life-size sculpture of the aforementioned Ms Campbell, and enter a highly interactive world that does much to explode the myths behind a largely impenetrable industry – which guards its privacy just as Knight strives to demystify it.

"SHOWstudio really came about because I thought my life was very interesting and very exciting," he says today. "And I couldn't believe that nobody else could see the things that I was seeing. That sounds very arrogant but it's not meant to be. Back in 1986 when I was photographing a very young Naomi and she was dancing to Prince in a bright red Yohji Yamamoto coat inspired by the collections of Christian Dior, I thought it was just so thrilling. It was a piece of contemporary theatre and it was seen by no more than around seven people. Fashion is such a fascinating world and if one could show the research that goes into a John Galliano collection, for example ... It's missed. Fashion is presented as something for the ladies or as trade. It's both scandalised and trivialised and it's a lot more interesting than that."

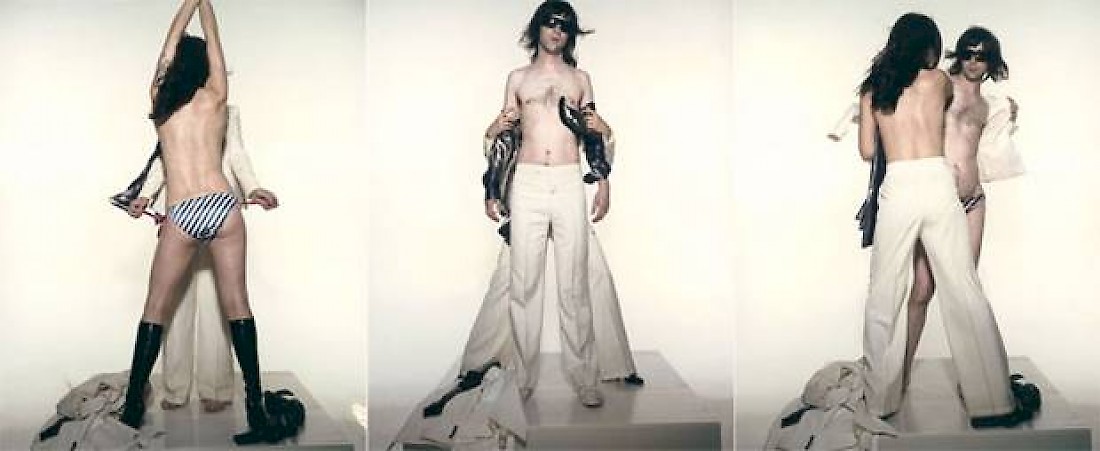

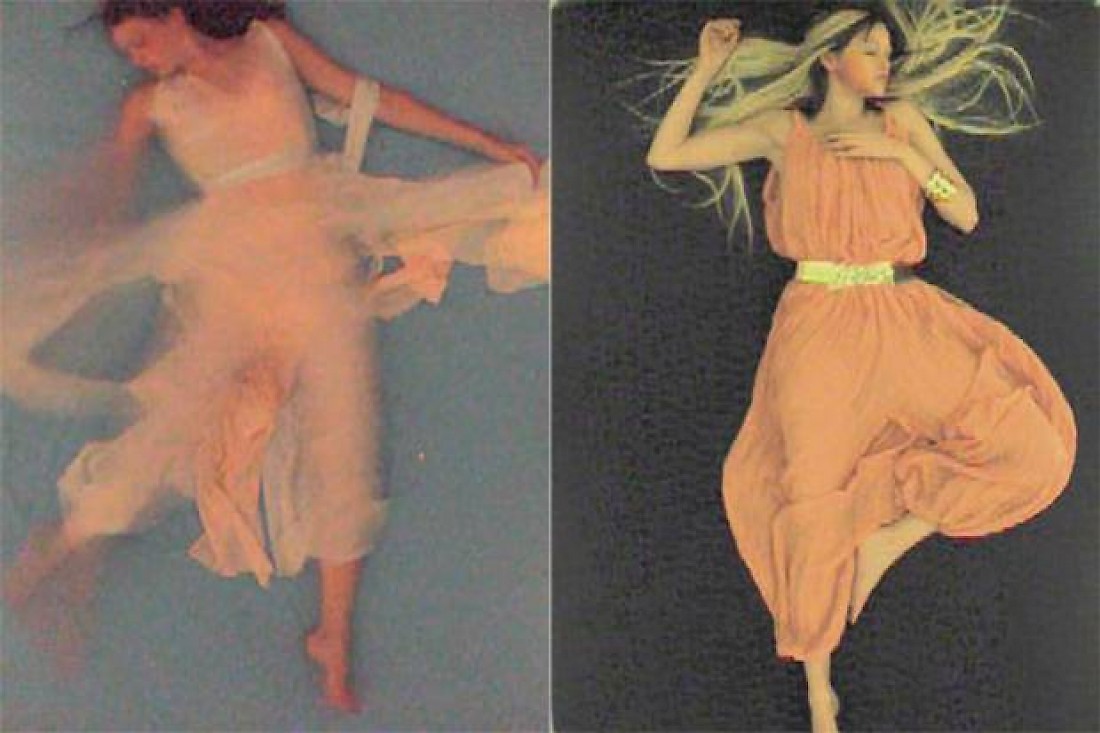

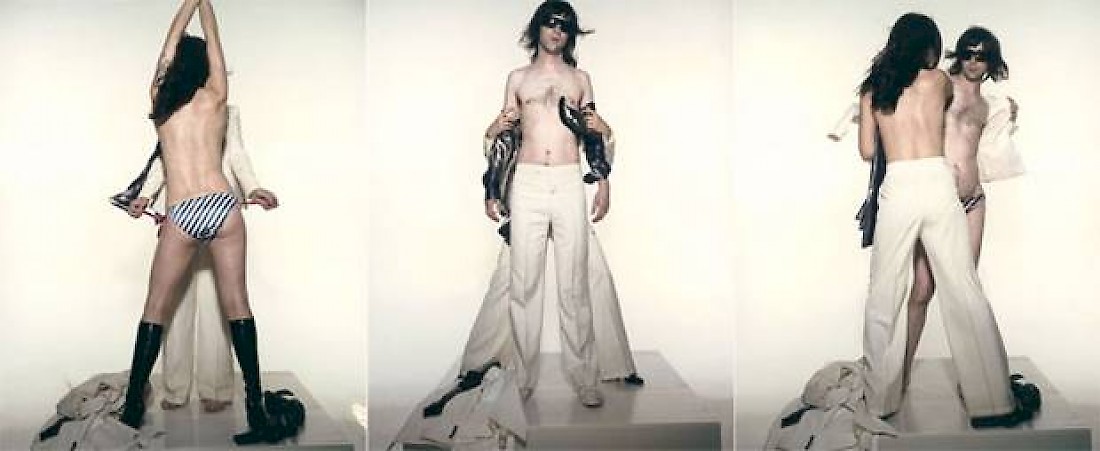

If they pick their time carefully, visitors to the exhibition will be able to witness Knight shooting for British Voguefirst-hand in a studio set up for the duration. At any moment, they will be able to watch fashion films that range from the quietly contemplative – some of the world's most fêted models are captured by webcam sleeping peacefully in a hotel bed, for example – to the rather more vigorous: the stylist Katy England and her husband, Primal Scream's Bobby Gillespie strip and change into each another's clothing before our very eyes.

"The internet is a very democratic medium," Knight told me on the eve of SHOWstudio's launch a decade ago. "I would have loved to have been there when Richard Avedon was shooting Dovima with the Elephants. All those great pictures that you see as one moment in time – but why not show the process, the really huge amount of work that has gone into achieving that?"

As is often the case with even the most respected artists, Knight's reasons for starting out on a career that would go on to become all-consuming were not entirely elevated.

"I first picked up a camera in about 1975," Knight says; he is 51 next month. "It was a family camera and the real reason I did it was because I wanted to photograph girls. I liked girls – it sounds really dumb, but then so did [Jacques Henri] Lartigue."

The fruits of any early interest, he says, are "these really embarrassing pictures that nobody will ever see" and his intention, at that time, was to embark on a career not as a photographer but as a doctor, the first step of which was to enrol for a course studying human biology at the Chelsea College of Science, then part of London University.

"I spent all of my teenage years assuming I wanted to be a doctor, but when I got to college I realised that, in fact, and almost too late, I had no interest in studying sciences whatsoever. I was kicked out after a year." Not long after that Knight found himself studying photography at Bournemouth and Poole College of Art, graduating in 1982.

His first major project was to document skinhead culture. "It was a rites-of-passage thing," he says today of the images that project spawned, "a reaction to my white, middle-class background." It wasn't long before he was seduced by the rather more obviously glamorous arenas of celebrity portraiture – The Psychedelic Furs, Bridget Fonda and Joanne Whalley were amongst his earliest subjects – and, more significantly, designer fashion, then beginning to realise the potential of its power.

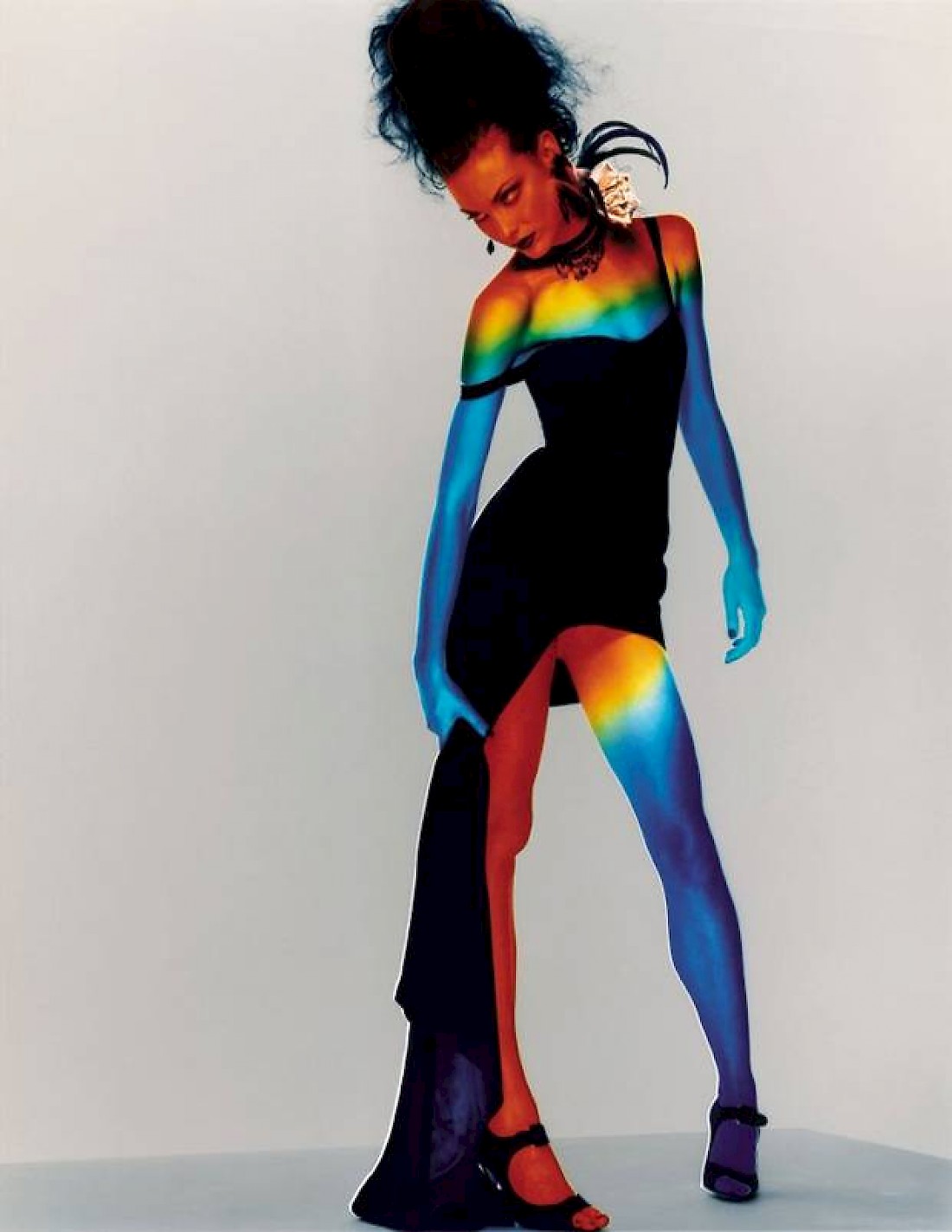

Central to everything that Nick Knight touches is a rejection of the great myth that the camera never lies. "What's reality?" he asks. "Where do you start? When Roger Fenton went out to the Crimean War to show the reality of the battlefields, he ended up dragging around the corpses to make a better composition. Originally, photography was seen as a better recorder of truth than painting – that's why it became popular. It's taken us 100 years to realise that actually that is not the case and neither should we want it to be. Photographers aren't machines that have no feelings and no opinions, they're storytellers; they manipulate the reality in front of them to tell you something interesting about it – and that holds true of everyone from Diane Arbus to Helmut Newton. That's why we keep looking at their work. The whole idea that photographers today are a bunch of deviant misfits producing pictures of people that somehow twist the truth in a malevolent way is ridiculous. Which camera you choose, which lens you choose, which lighting you choose, which angle you choose to shoot a subject from – all these things are crucial to the way that subject will ultimately be perceived."

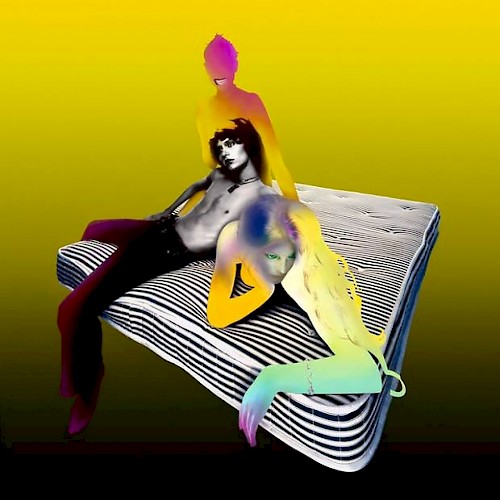

The birth of digital photography and the power of Photoshop image manipulation in particular have only fuelled the public's suspicions where any so-called distortion of reality is concerned. "But it's just a way of having more control," Knight argues, "and a lot more possibilities. It's a way of exploring the parameters within an image which is extremely exciting."

It would be all too easy for a photographer of Knight's status to rest on his laurels, but the opposite is the case. While there are those of his profession who mourn the passing of the printed photographic image, Knight simply sees technological advancement as an opportunity to advance with it. "You have to kill off your darlings," he says, "because once you find something you love it's wrong to keep working with that. I tend to move on. That's partly just because it seems like an interesting thing to do. I never feel that I fully understand anything, and that motivates me to keep trying. If you always work with the same tools, the same teams, the same ideas, it's like not being able to see a problem from another side. There's a certain amount of deliberate letting go that I have to do when I take on a project, because, if you're too much in control, you don't find out anything about yourself – you know what you're doing too well. There's that moment where you need to be discovering things by instinct – and you only really ever discover anything by instinct: when you're lost and you're having to fight your way back to be found again. If you don't do that, things become a bit too predictable."

The one thing that unifies Knight's work is an admiration for his subjects. "I tend to want to look up at people as opposed to look down at them," he explains. "My starting point is never critical. I would hate to think of myself as a sloganeering photographer. My political views are far from fully formed. All I know is that I view all people as equal. I do think, though, that if you attack people, moralise and lecture them, you tend to get a lot of hostility back. I'd rather just show that there might be a better way of being."

The men and women in particular in a Nick Knight photograph or film are, more often than not, idealised, or at least seen in their most inspirational form. That is not to say that he is responsible for adding to the deluge of super-glossy fashion imagery which is ultimately unattainable and therefore alienating. In the 1990s, Knight photographed Sophie Dahl – a figure distinctly on the large size given the stick-thin prototype model who tends still to dominate. He cast models aged in their 60s and 70s, black and white, for a ground-breaking campaign for Levi Strauss. In Dazed & Confused, meanwhile, he offered up images of a group of people with physical disabilities.

"My aim has always been to push at the boundaries of what is and isn't beautiful," he once told me. "Instead of our perception of beauty opening up, it's becoming more narrow all the time. To make money, the industry is increasingly catering to the lowest common denominator and, as far as the people who run the big companies are concerned, anything even slightly out of the ordinary frightens people. But anyone with a brain knows that it is the quirkiness and imperfection in a person that attracts other people. That is completely obvious to human beings; it's just when it gets to a corporate level that it all falls apart."

Over and above any ethically-informed motivation, however, the most important aspect of a Nick Knight photograph or film is his complete engagement with its creation on every level and from start to finish.

"From the moment I conceive an image to the moment it is completed, every step along the way, I am interacting with it, changing it, pushing my thoughts and beliefs on to it," he says. "That's as it should be. We want our artists to be thoroughly involved with their work and thoroughly in control of their craft, surely. We want them to have something to say."